2017 is a major election year in Europe. Election gains of populist parties could undermine support for European cooperation and threaten reforms.

Summary

- 2017 is a major election year in Europe. After the Dutch elections in March, voters in France, Germany, and possibly Italy will also go to the ballot box. In all four countries, populist parties are likely to gain.

- The election gains of populist parties could undermine support for European cooperation and threaten further economic reforms.

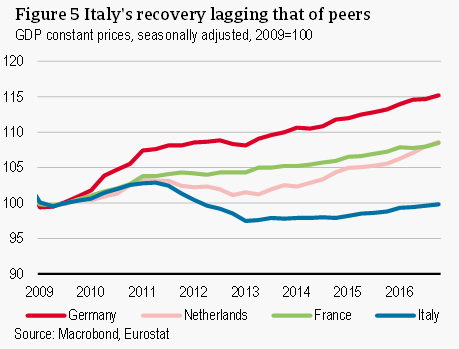

- Italy appears to be the most vulnerable to rising political uncertainty, given its subpar economic performance and widespread Euroscepticism.

European election year

The European political stage may change drastically over the course of 2017 with elections taking place in three – possibly four – key European countries. The March 15 Dutch elections have made the PVV of Geert Wilders the second-largest party in the Netherlands. Populist parties are also likely to be among the winners in the upcoming French presidential elections in April/May and the German federal elections in September. A similar scenario may also play out in Italy, where early elections are in the cards now that Matteo Renzi has resigned as both PM and as leader of the Democratic Party.

The populist insurgency places their anti-EU, anti-immigration voices at the forefront of European politics. Even if populist leaders fail to participate in government, their voices will be heard more clearly in the national parliaments. Among investors, this may trigger fears about the future of the euro and the EU. It may also cast doubts on whether countries with a strong political fragmentation can still implement the reforms that are needed. Here, we take a closer look at the political situations in these four countries in order to assess the likelihood of populist victories and to determine the implications this may have across various dimensions, such as participation in the euro, reform fatigue and access to credit.

Netherlands: fragmented politics

The Liberal Party (VVD) of PM Mark Rutte is the clear winner after the March 15 Dutch elections. The centre-right VVD received 21% of the vote and remains, by a substantial margin, the largest party in parliament. Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV), which campaigned on an anti-EU, anti-immigration agenda, came second in the election with 13% of the vote. Another four ‘mainstream’ parties received between 9% and 12% of the vote. Even by Dutch standards, this result reflects an unusual degree of political fragmentation. In total thirteen parties will enter parliament.

Given that at least four parties are needed for a majority coalition, the formation process will likely be difficult and lengthy. The VVD has started coalition negotiations with three other centrist, progressive parties. But with the political centre being fragmented, there are many possible coalition outcomes. This makes it very difficult to predict the exact composition of the next government. We can rule out a coalition with the PVV, given that not only the VDD, but also virtually all other parties have ruled out collaborating with Geert Wilders. Therefore, Wilders’ hopes for a referendum on EU membership are shattered. However, PVV’s power in parliament has increased and this will undermine the power base of mainstream parties. There are also wider European ramifications. This is likely to give at least some support to populist parties elsewhere in Europe.

France: elections wide open

The next test for populism will be the presidential elections in France. The presidential elections are held in two rounds, on 23 April and 7 May. If no candidate wins an absolute majority in the first round - the likely scenario - a second round will be held between the two candidates receiving the most votes. Eleven candidates are running in this year’s presidential elections. Three of them have a structural lead in the polls over the other candidates: Marine Le Pen of the Front National, François Fillon of the Republicans, and Emmanuel Macron who is running on his own platform (En Marché). Marine Le Pen is a critic of the EU, free trade and immigration. Her proposals include pulling France out of the euro, raising taxes on imports, to restrict immigration, lowering the retirement age and increasing several welfare benefits while lowering income tax. François Fillon is the centre-right candidate who campaigns on a deregulatory, socially conservative programme. He used to be the front-runner in the French presidential campaign, but lost a substantial share of the vote after being charged with embezzlement. Emmanuel Macron now holds the best cards to win the French elections, even though still a lot is possible. Macron is running on a pro-business and pro-Europe agenda crafted to appeal to both left and right. Leftist contender Jean-Luc Melenchon, who until recently seemed to have no chance of surviving the first round, has enjoyed a remarkable surge in the polls after strong performances in two televised debates, and is now just behind Fillon in the polls.

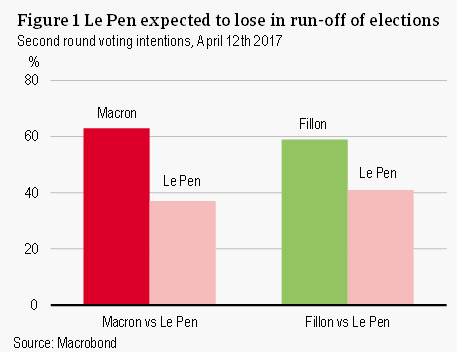

Should he continue in the race, François Fillon is predicted to attract under 20% of the vote in the first round. Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen are expected to receive about 25% of the votes each, which would lead to a second-round run-off in May to determine the next president. In the second round, Emmanuel Macron is expected to attract over 60% of the votes (Figure 1). His greatest vulnerability is that he has never run for election to any office before. Our base scenario is that Emmanuel Macron manages to rally enough voters behind him to become president, which would also mean that a French euro referendum is off the table. But the road to the French election could be bumpy, as the recent tightening of yields in response to the rising popularity of Jean-Luc Melenchon has shown.

Germany: Merkel likely to get fourth term

Federal elections in Germany are scheduled for 24 September this year. It is widely anticipated that the centre-right CDU will become the largest party, giving Angela Merkel a fourth term as Chancellor. However, Merkel’s junior coalition party – the centre-left SPD led by Martin Schulz – has surged in the polls. CDU and SPD are currently neck-and-neck, each drawing around 30% of the votes. Both parties are pro-European and have moderate views on immigration. The Alternative for Germany (AfD) party is the only German political party with strong anti-euro, anti-immigrant views. It is polling around 10% of the vote, which means it is almost certain to enter parliament. In 2013, it narrowly failed to cross the electoral threshold of 5% of the vote. However, AfD is not seen as a viable coalition partner by any of the mainstream parties. The most likely scenario is that the next government will again be a grand coalition between CDU and SPD. However, a minority government is also an option, given the reluctance of SPD to enter a grand coalition again as the junior partner. In any case, Germany’s participation in the euro is not threatened, given that both CDU and SPD are supportive of the euro.

Italy: possible snap elections in 2017

Italy is scheduled to have elections in May 2018. However, given the current unstable political situation, there is a conceivable chance that President Sergio Mattarella will call early elections in 2017. Former PM Matteo Renzi is hoping for snap elections in order to preserve momentum from his time in office. Current voting intentions put the Five Star Movement at around 30%, giving them a narrow lead over the Democratic Party. There is a reasonable chance that the Five Star Movement will become the largest party after an election. However, it is unlikely to get the majority bonus – bonus seats awarded to any party that gets at least 40% of the votes – and will therefore remain in the minority. The Five Star Movement is known for its anti-EU stance and its calls for control on migration. However, unlike the PVV in the Netherlands, Front National in France and AfD in Germany, it is left-wing rather than right-wing. The Five Star Movement also has milder views on migration than the other populist parties. It does call for a consultative referendum on membership of the euro.

Our base scenario is that the current Italian government will muddle through until the scheduled elections in 2018. After the elections, we expect there will emerge a coalition government of the Democratic Party, the centrist parties, and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. Another possible scenario is that of a minority coalition, but this again is not likely to include the Five Star Movement. To force a referendum on the euro, the Five Star Movement would need to secure a two-third majority in parliament. They might achieve this if they receive backing from other Eurosceptic parties, such as Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (or radical elements within this party), the far-right Northern League and the national-conservative Brothers of Italy. The ideological differences between these parties are large, but a scenario in which they collaborate to force a referendum on the euro cannot be ruled out completely.

Common themes across European elections

Running as a common thread across these election campaigns are European cooperation and immigration. Populist parties have placed these themes at the centre of their election campaigns.

European cooperation

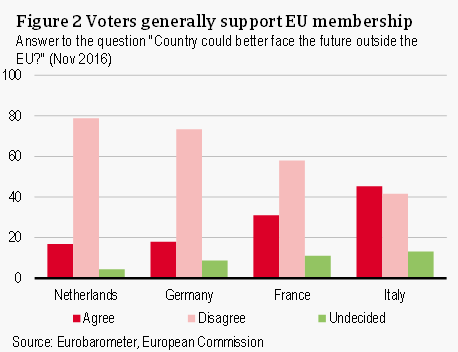

Anti-EU rhetoric plays an important role in the campaigns of populist parties. They are tapping into a widespread critical sentiment towards the EU. In the Netherlands and Germany, the vast majority of voters would oppose an exit from the euro and the EU. However, there are concerns with how the EU is functioning, whether it be about bureaucracy, eastern enlargement, or the handling of the migrant crisis. In France, a smaller, but sizeable majority of voters are supportive of the euro and EU membership. Polls show that two-thirds of French voters are against a euro exit. Italy is the only country where anti-EU and especially anti-euro sentiment is widespread (Figure 2). But even there voters may very well back down from leaving the euro when faced with the immediate chaos that would follow such a move.

Immigration

The other major theme in Europe’s elections is how to deal with the strong rise in immigration from non-EU countries. According to Eurobarometer survey results from November 2016, immigration tops the list of issues that EU citizens perceive as the biggest challenge to the EU. Immigration is also at the centre of election campaigns of the far-right, whether it is Geert Wilders (PVV) in the Netherlands, Marine Le Pen (Front National) in France, Frauke Petry (AfD) in Germany or Matteo Salvini (Northern League) in Italy. Far-right populist parties have also forced politicians from centre-right parties to adopt a more critical stance towards immigration in an attempt to not alienate voters.

Economic effects of political uncertainty

The rise of populism in Europe comes with some important risks. One is that it threatens to undermine the political support for the eurozone. Another is that a populist victory may stifle reform-making. This risk of policy fatigue is particularly large for France and Italy, which suffer from structural economic weaknesses. These risks play out over the medium to long-run, but have potentially significant downside economic effects.

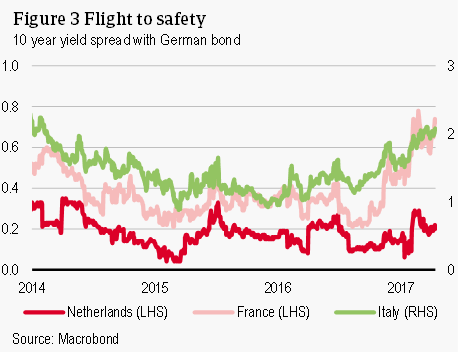

In the short-run, the economic effects of political uncertainty seem to be small, as the Eurozone economy is on a much stronger footing than a couple of years ago. Nevertheless, forward-looking financial indicators like government bond spreads can offer some indication as to how financial markets anticipate a populist victory. The spreads of French and Italian 10-year government bonds vis-à-vis the German bond are currently 72 and 2008 basis points (Figure 3). Looking at the development in yields, there seems to be a connection between movements in the French yield spread and the upcoming elections. The French sovereign spread peaked in late February, when news stories were published about ‘mainstream’ candidate François Fillon being charged with embezzlement. The situation is somewhat different for Italy, whose sovereign yields have been increasing gradually since mid-2016. The rise in Italian yields can be traced back to a combination of political risk and more general worries about subpar economic performance.

The economic implications of higher yields in France are not expected to be large in the short-run. However, if the higher yields were to be persistent, they would translate into higher borrowing costs for companies and a weakening of investment in the medium-term. The pressure on French yields had been easing until recently as the chances for Mr Macron to become president were improving. But now that Jean-Luc Melenchon is rising in the polls, they are increasing again, given his controversial economic agenda and critical stance towards Europe. Nevertheless, the development of yields in Italy is still much more worrisome. Compared to mid-2016, yields are now almost a full percentage point higher. According to ECB Bank Lending Survey data, business demand in Italy for credit has been weakening already from early-2016. While household demand for loans (consumer credit & other lending and loans for house purchases) is showing no signs of weakening yet, yields have risen to such an extent that this may be impacted as well over the coming months.

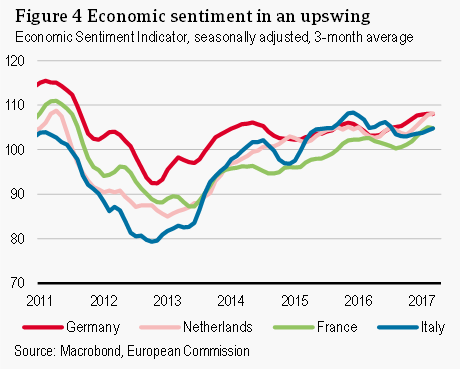

In Germany, France and the Netherlands, the Economic Sentiment Indicator (ESI) has been in an upswing over the last couple of months. The same is true for a separate indicator on consumer confidence. In Italy, confidence indicators have been ticking up in recent months, but this seems to be an aberration from a longer term declining trend. The rise in sentiment indicators should encourage higher consumer spending and investments in the future, which supports GDP growth.

The Eurozone economy has weathered the political uncertainty well, thanks to a combination of accommodative monetary policy and low inflation which boosts the spending power of consumers. The economic recovery is well under way, with Eurozone GDP expanding for fifteen quarters in a row. There is also a clear upward trend in GDP in all the election countries. At the same time the Eurozone recovery is still progressing at two speeds, with formerly stressed economies such as Italy, Portugal and Greece lagging behind.

The precarious state of Italy’s economy makes it a target for capital flight if political uncertainty continues to rise further. The widespread Euroscepticism means that if it would ever come to a referendum on the euro, a ‘leave’ vote is not unthinkable. This makes Italy the most vulnerable of the four European countries with elections approaching. Any news pointing to better election chances for the Eurosceptic Five Star Movement could lead to a further rise in sovereign yields, a postponement of investment and a weakening of business and consumer confidence.

Populist parties undermine political stability

The Netherlands, France, Germany, and possibly Italy, are having general elections this year. In all four countries, populist parties are likely to gain compared to previous elections. While we do not think that any of these populist parties will actually be elected into leadership, their anti-EU stance will be heard more clearly in national parliaments. Furthermore, they are also likely to oppose economic reforms more strongly than the mainstream parties, which is worrisome especially for Italy and France. Based on financial and economic figures, it is evident that Italy should be watched most closely. Any sign of rising support for populist parties there may lead to a rise in yields, lower confidence and delayed business investment.