One year after the UK vote to leave the EU, cracks are beginning to show in the economy. This Atradius report offers an update on the current situation and insolvency outlook.

Main conclusion points:

- The UK economy has been remarkably resilient since the vote to leave the EU, but one year on, growth is being increasingly challenged. Inflation is the main culprit as real wage growth has turned negative, squeezing household purchasing power.

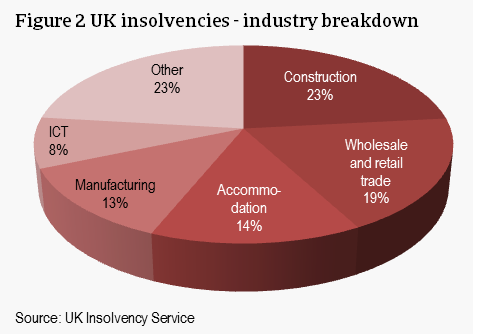

- UK insolvencies have been rising since Q3 of 2016 and are forecast to increase 6% this year and 8% next year. Business failures are expected to be concentrated in consumer-facing sectors like retail and accommodation and those that depend on imported materials like construction.

- Effects on the rest of Europe have been limited so far, especially as domestic politics have thus far bucked the trend towards populism, easing uncertainty. But we still forecast insolvencies in 2017-2018 to be higher in Europe than if there was no Brexit, particularly in those countries with close economic ties to the UK like Ireland, the Netherlands and Belgium.

UK economy: resilient and stable, but inflation beginning to bite

In the aftermath of the 23 June 2016 decision to leave the EU, the UK economy has been surprisingly resilient. After an initial shock, confidence quickly rebounded and consumers continued to support solid economic growth. A sharp depreciation of the pound sterling also contributed to higher growth, boosting manufacturing exports in particular. But now the flipside of the weak pound sterling is beginning to ease momentum as it weighs on consumer spending.

The pound sterling has depreciated about 14% relative to the euro and USD compared to June 2016, with most of the adjustment taking place directly after the referendum. This increases the costs of imported goods, which, coupled with the recovery in oil prices since early 2016, is driving up prices. Annual consumer price inflation has reached 2.7% in April 2017, the highest level since August 2013. Despite the lowest unemployment rate in over 40 years (4.6%) and robust employment growth, wages have not kept up with inflation, in part due to relatively low productivity growth. In March 2017, wages grew only 2.1% y-o-y, suggesting a contraction in real wages, or decreasing consumer spending power.

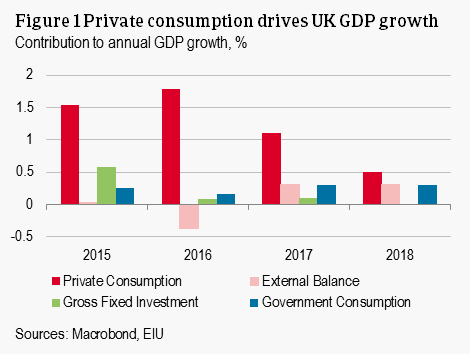

Private consumption drove 1.8% GDP growth out of a total 1.8% growth experienced in 2016 (net exports cancelled out the small contributions of government consumption and fixed investment). GDP growth slowed to 0.2% q-o-q in Q1 of 2017, down from an average quarterly rate of 0.6% in 2016 and marked the slowest pace in four years. As expected, the slowdown is concentrated in consumer-focused industries like retail and hospitality (though this should be partially offset by higher foreign visitors to the UK, attracted by the weaker pound sterling (+4% in 2016). This comes at a time of low household savings rates – only 3.3% in Q4 of 2016. Furthermore, in 2017 consumer credit conditions are expected to tighten for the first time in six years.

With low savings, tightening access to credit, and slipping real wages, private consumption is forecast to slow in 2017 but remain positive. It is expected to fuel 1.1% growth in GDP in 2017. Higher government consumption and a positive contribution from the external balance, thanks to more competitive exports, will help to keep annual GDP growth stable around 1.7%. Business investment has held up better than expected, but still slowed to 0.5% y-o-y in 2016, from 3.4% in 2015. It is expected to be stable in 2017, in part due to the long-term nature of most investment. However, as negotiations with the EU heat up, we expect uncertainty to play an increasingly negative role, halving private consumption’s contribution to GDP and bringing growth from investment to a standstill in 2018.

To read on corporate insolvencies and impact on EU, please download the full report below.